An important aspect to interesting enemy AI is the way in which enemies are determined to be aware of the player, usually by the use of senses. Just as important is how they react once they no longer have a sense of where the player is.

Researching into this, I found Mark Botta’s chapter “Infected AI in The Last of Us” in Game AI Pro 2. It included much about how sight and hearing worked in the game, as well as how the infected AI would “freak out” once it lost track of where the player was. Looking more into The Last of Us’s approach to the topic, the chapter after about Human Enemy AI by Travis McIntosh discusses how they would search for the player after losing them, with his GDC talk about the topic contributing a lot more technical detail.

These four things (sight, hearing, infected freakouts, and searching), are the main focus of the article. I worked in Unity to recreate these parts of TLOU’s AI, and this article will break down how each of these aspects work (or at least how I did it). The repository for my tech demo can be found here, but please note: although this successfully uses and demonstrates most of what this article discusses, none of this code should be ripped from directly for a game. Your time is better spent taking from how I’ve outlined the system to work in this post and applying it to better architecture.

AI Awareness

There are two senses that the demo simulates (and the resources mentioned about TLOU’s AI): sight and sound. In TLOU, values store how long an enemy has seen a player, going up as the player is in view and down as they aren’t. If it reaches a set threshold of time, the enemy is considered to be aware of the player. This threshold changes depending on the behavior state of the enemy (ex: enemies amid combat have a significantly lower threshold) and the (ex: infected with damaged vision have a higher threshold than the human AI). In my tech demo I also made a threshold for time hearing noise from the player before an enemy is determined to be aware of them, though I read nothing that explicitly said Naughty Dog did the same.

Sight

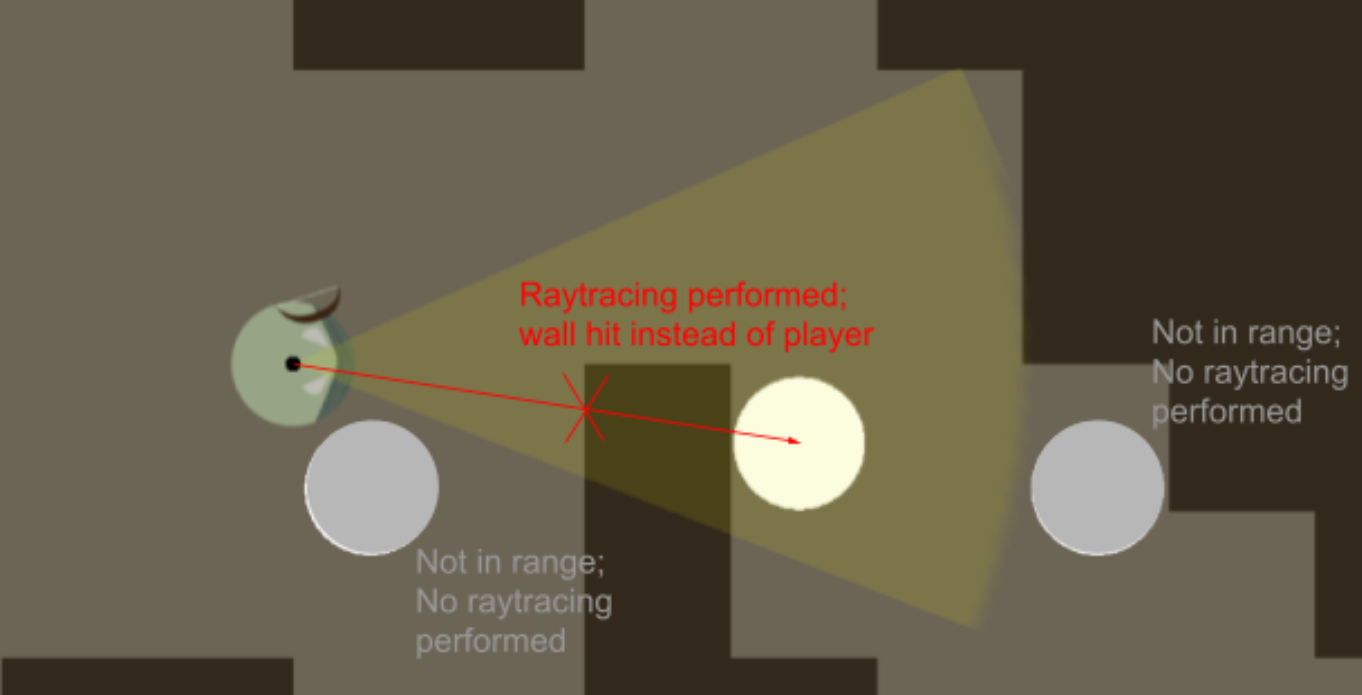

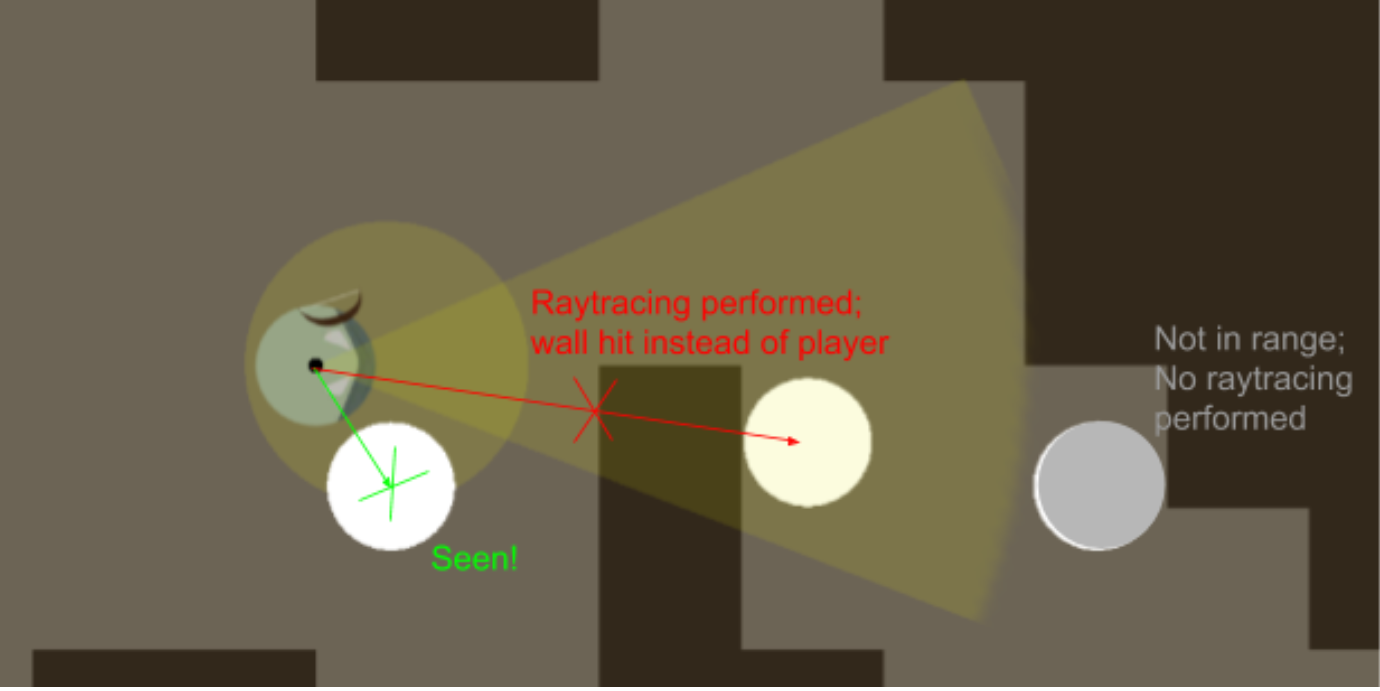

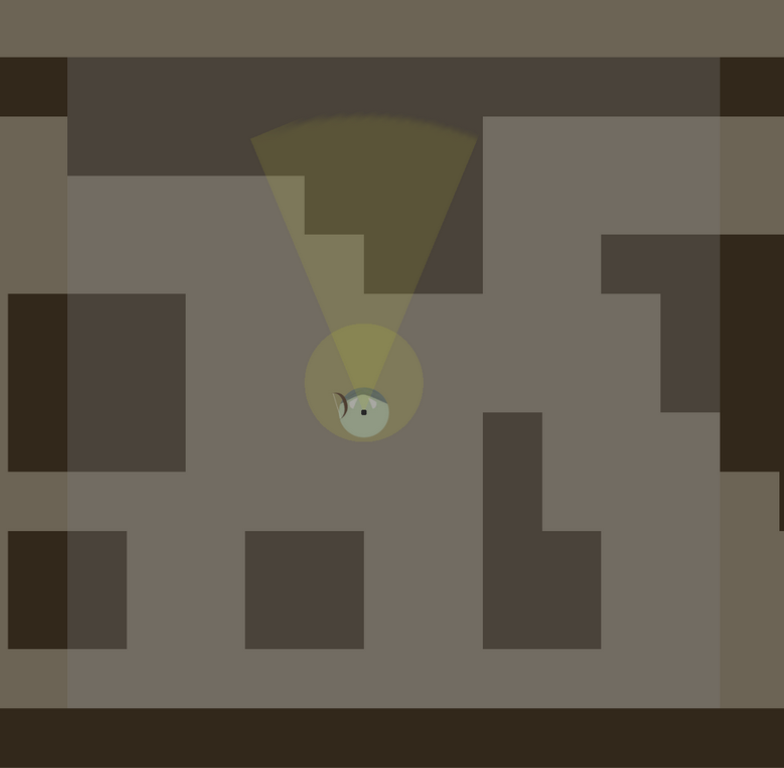

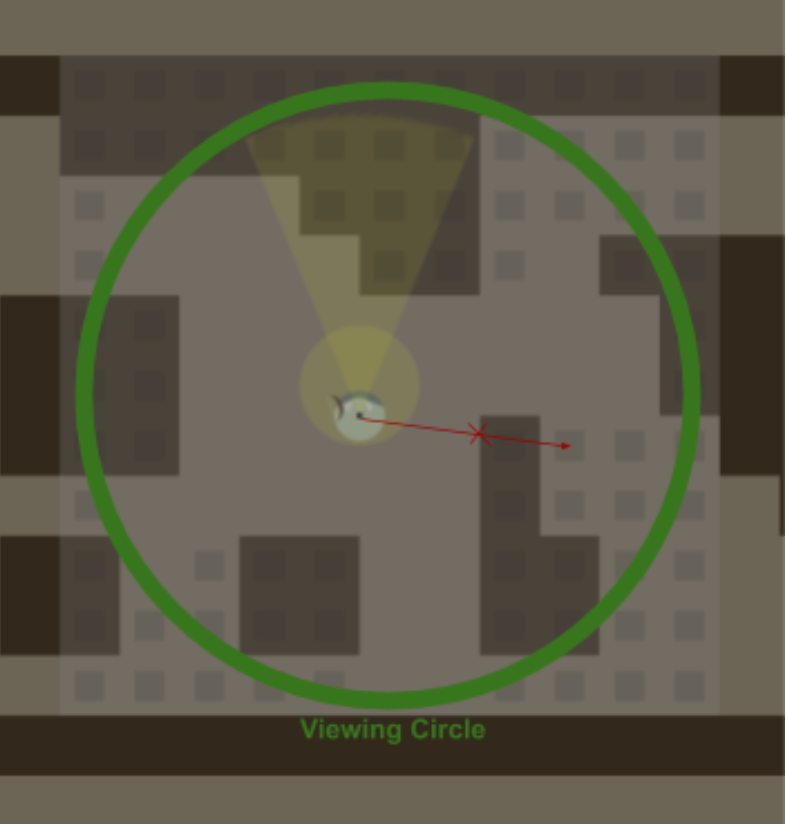

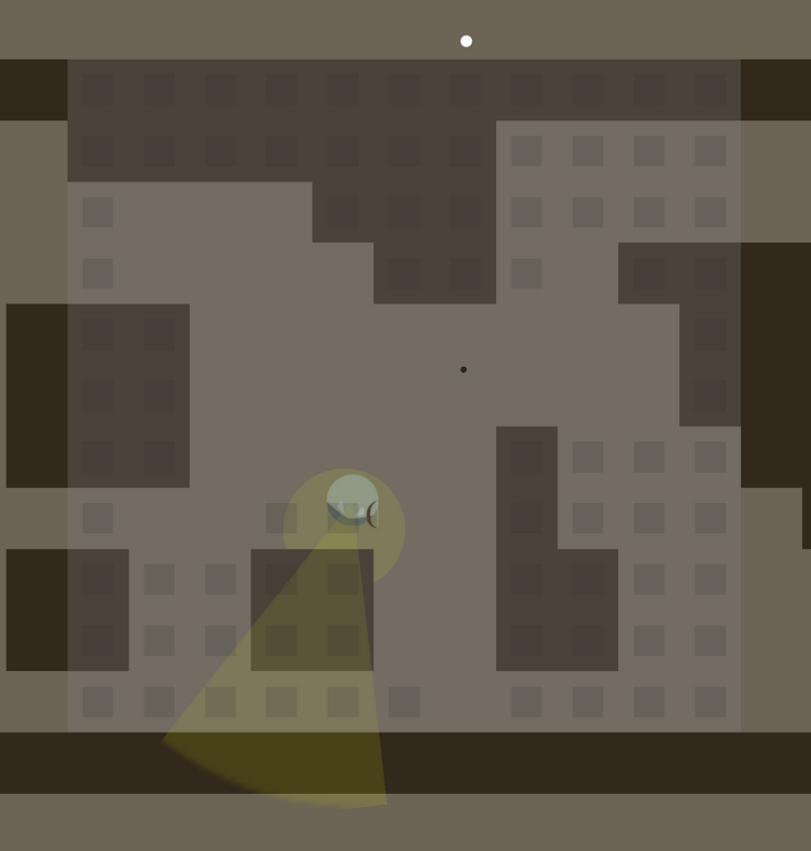

Sight in many games is achieved by the use of vision cones. These work by performing a ray cast from the enemy’s location towards the player and testing if anything gets in the way. Raycasts are expensive, however, so the enemy first detects if the difference between the player position and enemy position is in a set distance and angle difference from the where the enemy faces.

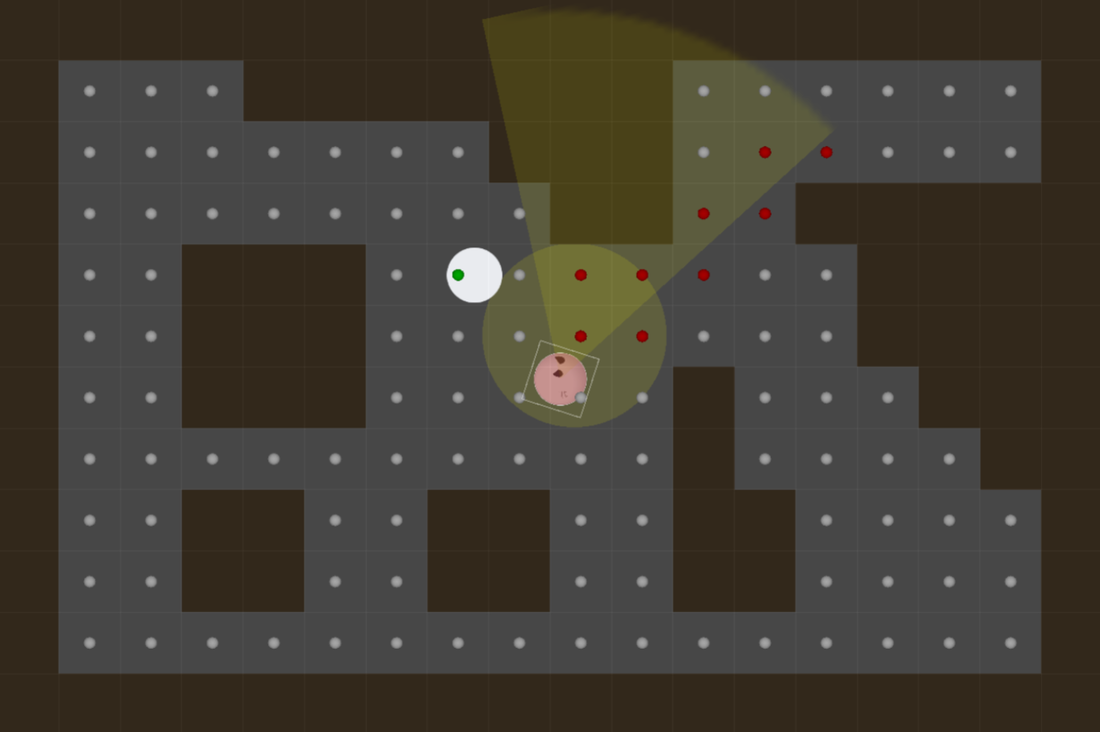

However, one issue with this system is that it’s hard to have a reasonable angle that works at all distances. If a player were to stand right to the side of the enemy, they wouldn’t be seen, but if the angle is too wide, an enemy will spot the player way off to the side from a far distance. In TLOU, the developers adopted a principle that “the angle of view for an NPC is inversely proportional to distance” to make a custom vision shape. If you look below, the added vision area allows the enemy to detect and raycast the player to the side of them. Naughty Dog’s vision shape was more complex than what’s in my tech demo (they never disclosed the specifics), but you can see there’s an improvement just by having this extra circle.

Hearing

Through sound, Enemy AI becomes aware of the player in two ways:

- Any loud enough sound from the player

- Noticeable noise from the player for a set amount of time (as mentioned in “AI awareness”)

Both the volume level that is “loud enough” and “noticeable noise” are custom values that can differ between AI behavior state and type (just like the thresholds). The volume a noise gives off could be determined by a simple lerp based on distance away, or something more complex—Mark of the Ninja only has a guard hear if an A* path to them doesn’t leave the intended radius of the sound’s travel.

Infected Freakouts

Now that we’ve touched on how the enemy can become aware of the player, there’s a question of what the enemy should do if they’ve lost that awareness—how they should react. This may be a question of how you want your enemies to come off as. The infected in TLOU are supposed to feel erratic and inhuman, so Naughty Dog’s approach was to have the enemy look around erratically in a set space for a little before going back to wandering. The technical process is as follows:

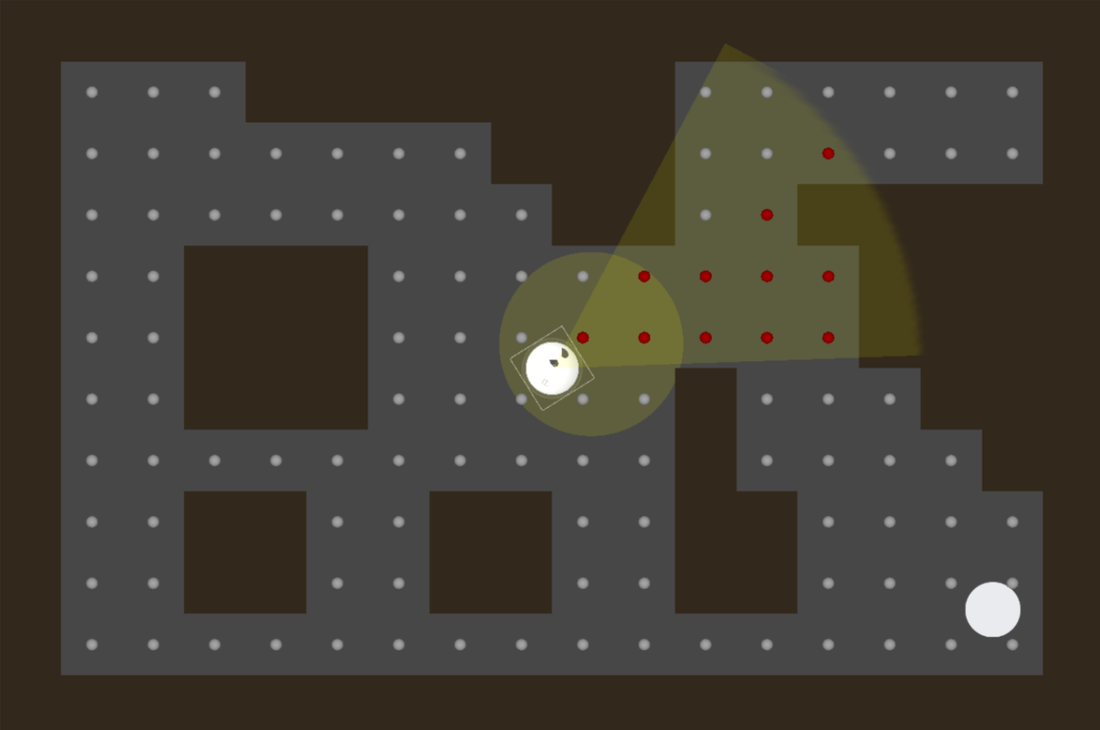

- Spawns in a square grid around the enemy

Tiles are marked as “seen” (represented by the black marks) out if they are

- not in the viewing circle (which has the same diameter as the square’s length)

- is inside a wall,

or - are obscured from view by a wall (checked using raytracing).

- A new location/animation is picked. In TLOU, the end positions/rotations of a number of animations would be calculated, and from there a priority queue would be made taking into account how many “unseen” tiles the end point of the animation would be facing (and if the animation had already been played). I am not an animator, so instead my tech demo chooses a random “unseen” tile for the enemy to travel to.

At the end of the animation/traversal, all of the “unseen” tiles in the enemy’s view at that moment are turned into “seen” tiles.

Repeat starting from step 3 until enough time has passed or all tiles have been labeled seen.

After that point, the infected enter a more neutral state, having lost its stimuli.

Exposure and Search Map

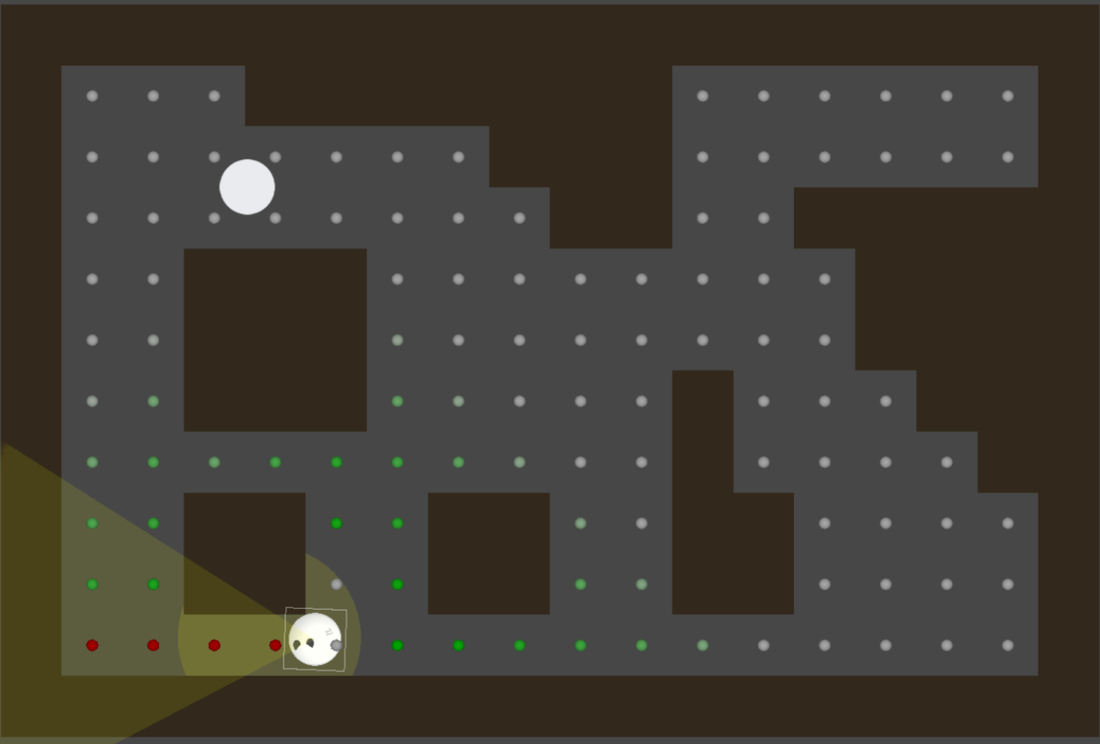

When going against human combatants, it would be expected that they would attempt to find the player once they’ve lost awareness. In TLOU, this is achieved with the use of an exposure and search map. An exposure map is a tile map over an entire level that updates every second to show what tiles of the level are exposed to the enemies (shown in red).

The search map keeps track of what are the most likely spots for the player to be in when the enemies are trying to find them. When the enemies are aware of the player, only a single tile of the map is marked: the player’s location (shown in green).

Once the enemies lose the player, they all enter a search behavior, and the search map will take from that green point (the last known location of the player) and eventually spread it out across the map—note the gradient of green to white. Each of these tiles have a distanceFrom value that states how many tiles removed it is from the original tile (the original’s value being zero).

An important thing to note is that each time the exposure map is refreshed, any exposed tiles will be cleared off the search map—note the cleared tiles next to the enemy. They still contribute to the spread of the search map, but the AI considers that tile already searched.

To perform searching, the enemy AI’s will determine which unsearched tile to head towards. In my demo, I used a priority queue in which the priority was determined by the sum of the tile’s distanceFrom value and the AI’s distance from the tile itself. After reaching that point, a next point is calculated. The result is that AI walks down a hallway for some time, eventually turning around to check another one the player could have gone down. Over time, the AI will continue to spread out. It transitions from searching the immediate vicinity to eventually sweeping the entire area.

Applicability

This isn’t a necessity for every game out there; any game with constant combat or a simple area in which it’ll be activated won’t require anything we’re mentioning. Even if it uses senses to trigger interaction with the player, unless a game intends to have the combat turn off once it’s been turned on, it doesn’t require the second part of this post’s focus. However, games with stealth elements or enemies that are intended to feel real should have something like this. To quote Mark Botta: “the best way to achieve these goals is to make our characters not stupid before making them smart.”

As hilarious as it is, an enemy going back to their patrol saying “must have been the wind,” after getting shot in the neck with an arrow is going to break a player’s immersion with a world devs made to get lost in.